I began my Unit 1 research by exploring the notion of the uncanny, a term I have been associating with my artwork for several years now. Looking at my portraits, it seems clear to me that there is indeed an uncanny aspect to them, though perhaps not in the art definition of the term, but the one I had come to understand from literature classes in the past. The notion of the uncanny in the art world has primarily come to refer to what Freud, quoting Jentsch in his essay The “Uncanny,” explains as “a particularly favourable condition for awakening uncanny sensations” in the instance that “there is intellectual uncertainty whether an object is alive or not, and when an in- animate object becomes too much like an animate one.” (Freud 1919, p. 8-9). As it was impressed upon me during one of our Unit 1 groups, I realised the importance of defining the words I associate with my artwork. Therefore I will use the word uncanny in its most simple definition, referring to “all that is terrible—to all that arouses dread and creeping horror; it is equally certain, too, that the word is not always used in a clearly definable sense, so that it tends to coincide with whatever excites dread” (Freud 1919, p. 1). It is with this in mind that I practice painting and use the notion of the uncanny as a basis for my artwork, aiming through various artistic means such as cropping, lighting, and composition to create an eerie, uncomfortable atmosphere in my painting.

Gregory Crewdson, Father and Son, 2013.

Following one of the first tutorials, where we spoke about the notion of voyeurism and the creation of atmosphere in art, I began to research Gregory Crewdson, an artist whose work I found out is also heavily influenced by Freud’s essay on The “Uncanny.” I felt that Crewdson really encapsulated the feeling I was attempting to convey in my portraiture. The image I find particularly fascinating is Father and Son, in which our eye is drawn first to a man lying in bed, then to the reflection of who we presume is his son in the mirror. This image is bathed in an eerie grey light, and is suffused with a mysterious stillness. It perhaps one of the best examples of “a classically enigmatic Crewdson image, another condensed story ‘both open-ended and ambiguous’" (Glass 2017, para. 9). Another aspect of Crewdson’s work which I found relevant to my own was the way he sets up a scene makes the viewer feel uncomfortable, because we are often looking into what seems to be an intimate moment: “Crewdson is a master of atmosphere. The characters who inhabit these stilled moments seem marooned in their own thoughts to the point of torpor” (O’Hagan 2017, para. 9). This in turn makes us as the viewer feel uneasy but also draws us in, in the way that stumbling across something we should not be seeing makes us as humans unable to look away.

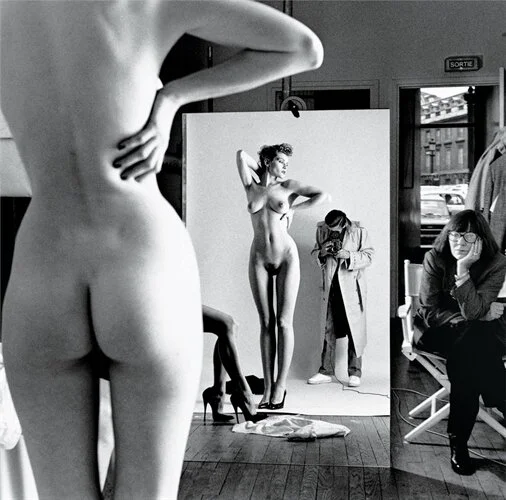

Helmut Newton, Self-Portrait with Wife and Models, 1980.

One has only to look at art history to know that the idea of voyeurism as a tool to draw in the viewer has existed for a long time. For example, a painting like Hylas and the Nymphs by JW Waterhouse could be considered voyeuristic for the depiction of young nude women in a pond. The invention of photography has added another element to this idea of voyeurism:

One of the most complex questions raised by photography is what constitutes private space, provoking slippery questions about who is looking at whom and the degree of surreptitious pleasure and exploitation of power involved. Since its invention the camera has been used to make clandestine images and satisfy the desire to see what is normally hidden or taboo. (Hubbard 2010, para. 2)

JW Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896.

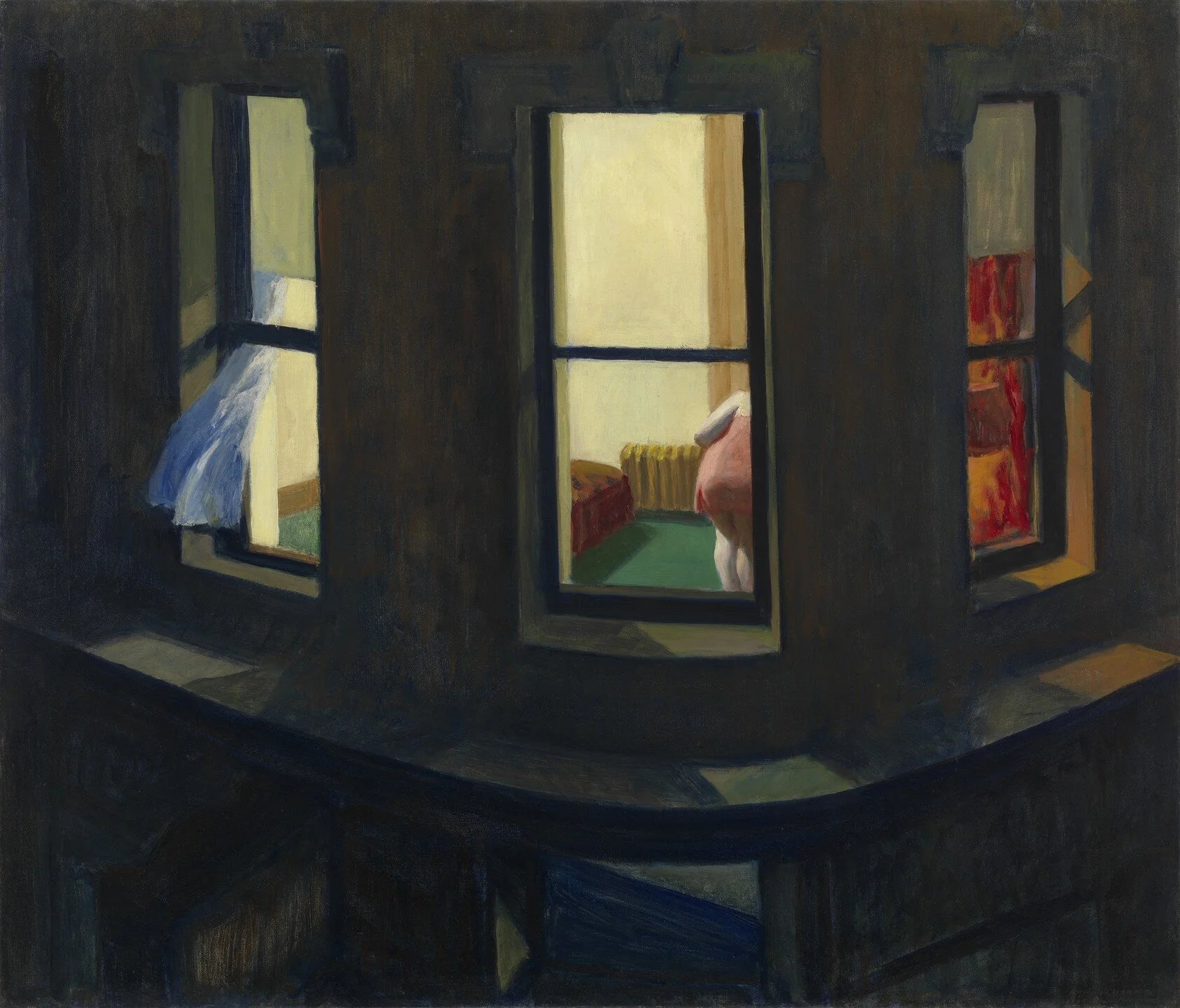

Although this applies here to photography, I find it very relevant to my practice since my process involves staging photographs which I then use as sources for my painting. This idea of photographic voyeurism is also found in contemporary paintings such as Night Windows by Edward Hopper. The composition, where we as viewers are looking into a series of windows, lit up in the night, places us immediately in the position of voyeurs, peeping into a private moment. Here, the reading of the private moment is deliberately ambiguous. We are given a snapshot of this window, but what the woman in the frame is doing is left to our imagination to complete. Like, Crewdson, who is also influenced by Hopper in his work, there are cinematic elements here which enhance the desired effect:

This seems a particularly cinematic painting, with its glimpse of nocturnal activity mirroring the voyeurism of watching in the movie house. The frames of the window suggest a film strip, while the theatrical curtains reveal the show. (Sherwin 2018, para. 3)

Edward Hopper, Night `Windows, 1928.

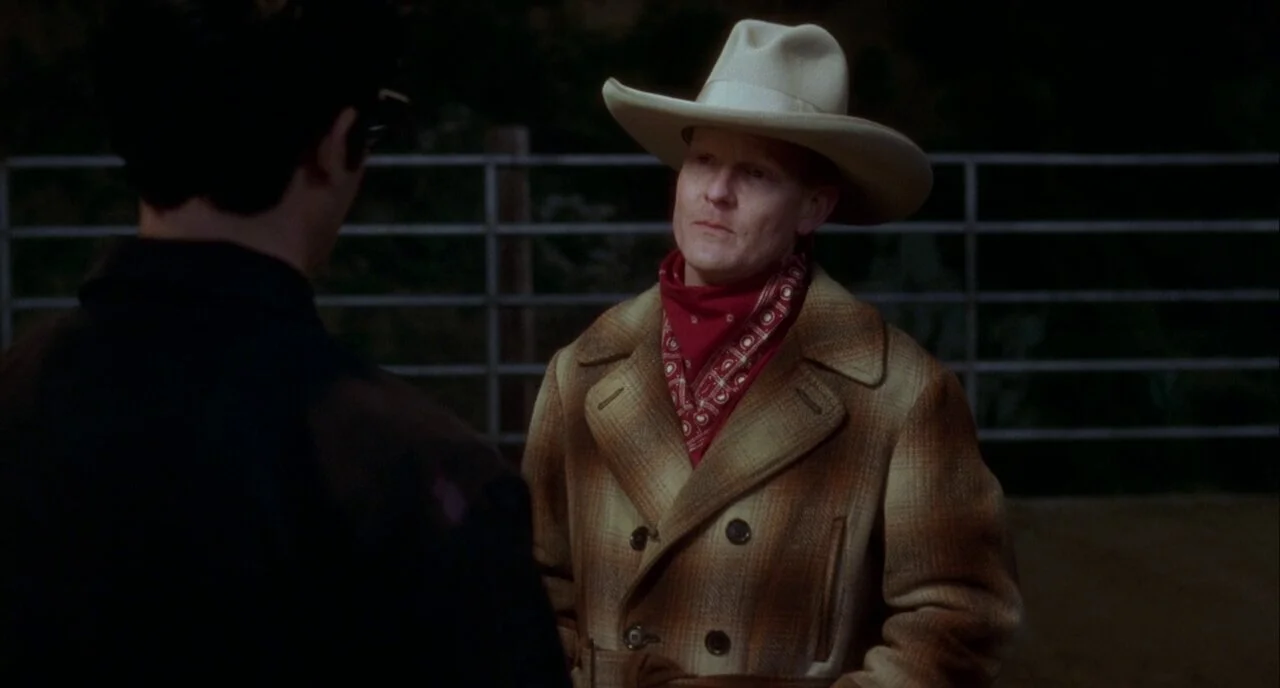

Another influence on my first painting was the television show Twin Peaks. I had always been familiar with it and enjoyed it for the atmosphere it created, but this rewatch allowed me to see how David Lynch used filmic elements to throw off the viewer. One particular scene that has stuck with me, in one of the first episodes, is when the mother of a missing girl realises her daughter has not been home since last night. She runs up the stairs to her room, and the camera is placed at the bottom of the stairs, in the corner, creating a shift in perspective which enhances this already anxiety filled moment. This is just one example of the techniques Lynch uses in his “trademark style: his idiosyncratic offbeat cinematography-hand-held obscure point of view shots, superimpositions, shaky focus, etc-, lighting-more atmospheric than communicative” (Willemsen & Kiss 2019, p. 138).

Mark Frost and David Lynch, Twin Peaks, 1990.

With the influence of these sources, I began preparing for my first painting. My process begins with an idea of a composition, which I sometimes sketch out roughly. My primary source for my paintings is the photograph. Once I have an idea in mind, I ask my subjects to pose for a series of photographs, then choose the one with the most interesting aspect. Lighting is extremely important to me, and I do not leave that element to chance in my paintings. I use a single light source (blocking out any natural light from the room) to create harsh shadows on the faces, in a chiaroscuro fashion. This methodology to me is similar to the way a director might use lighting in a film noir. For example, in the neo-noir film Mulholland Drive, “by emphasising the interplay of light and shadow, Lynch interjects a sense of mystery […] while at the same time heightening our sense of reality in his visual narratives”(Nieves 2020, para. 3). I would venture to say that this particular lighting techniques is crucial to the creation of atmosphere in this film.

David Lynch, Mulholland Drive, 2001.

David Lynch, Mulholland Drive, 2001.

There is a lot of thought that goes into the photography stage of my painting, which is why I relate so strongly to Gregory Crewdson’s work. He is notorious for his budget, and lengthy process. His series, Cathedral of the Pines (2016):

took two and a half years to shoot and, typically for Crewdson, required the kind of preparation that usually attends a Hollywood film: months of casting, location hunting and storyboarding, with an extensive crew to oversee lighting, props, wardrobe, makeup and even some special effects involving artificial smoke and mist. (O’Hagan 2017, para. 4)

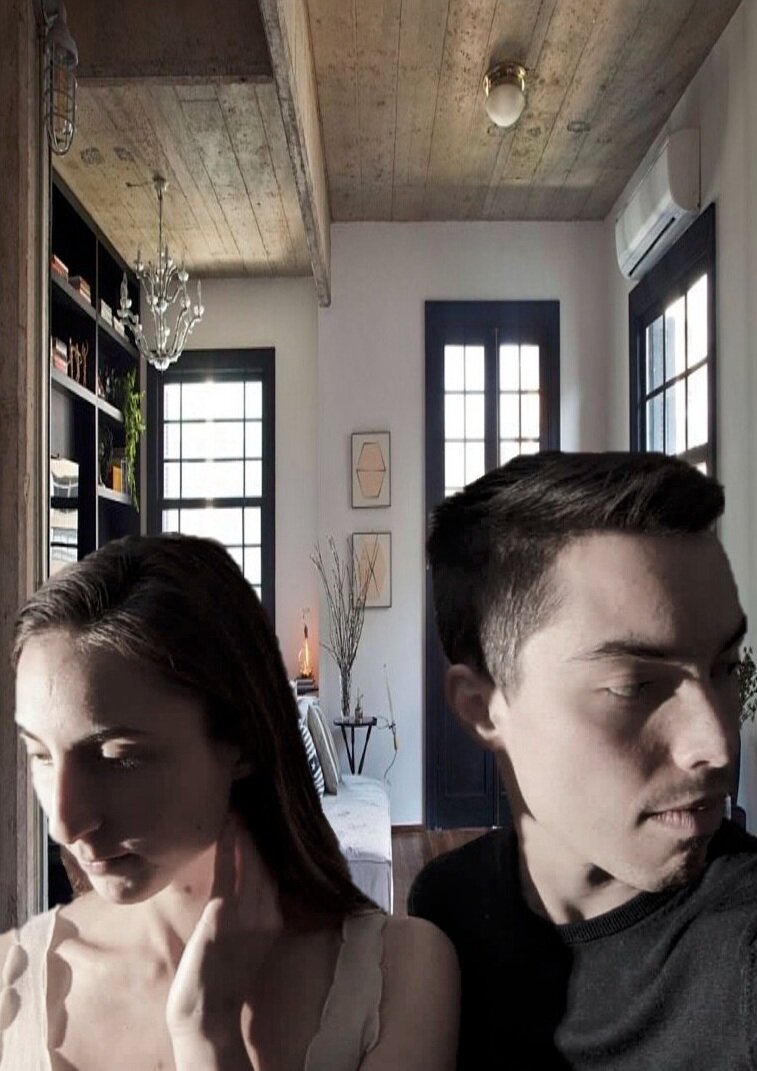

Once I have the photograph, I begin to paint, first projecting my image onto a canvas and doing a detailed underpainting. This stage helps me to ensure I have blocked out the areas of light and dark so that the atmosphere is not lost. In this painting, I decided to do a collage, as I became interested in how the background of a painting could influence the figures in the portrait (see image below). This was in part inspired by Crewdson, where the things surrounding the figure are instrumental in creating a narrative in the image, particularly in Cathedral of the Pines, where these “individual souls who seem lost and adrift despite the trappings of home and material success” (O’Hagan 2017, para. 7). In my research, I also came across an analysis of the significance of objects in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, and the one which struck me particularly for its mundane aspect is the ceiling fan:

Like the traffic light swinging in the wind, the image of the fan at first seems simple atmospheric- a detail used cinematically to create a strong sense of place. Yes, through precise repetition, the image gains narrative significance. The fan appears in the pilot episode when the viewer knows that Laura is dead, but Sarah still does not. (Sheen & Davison 2004, p. 99)

The inclusion of the mounted fan in my painting (see image below) however threw seemed to throw people off in my painting, with many wondering if it was a necessary inclusion. In light of the previous quotes I think it was necessary to the narrative of domestic disquiet built by my image.

Preparation for the painting, digital collage from found imagery and photograph taken by friends, directed by myself.

Untitled, oil on canvas, 60x90 cm.

During the first group critique, many people commented on the way the lighting and composition of my work reminded them of cinematography. The empty space left in the centre of the canvas and single light source made them feel like this was a dramatic psychological portrait, which made them feel uncomfortable as viewers. One person described the composition as Kubrick-esque, relating to Stanley Kubrick’s direction style. As I had been watching Stanley Kubrick films while painting, I found it intriguing that he had influenced my painting perhaps subconsciously. The following video explains how Kubrick uses symmetry and the one-point perspective to make a shot more picturesque, and how he uses the zoom in effect to build tension, much like a painter might crop an image to achieve a similar effect (Stanley Kubrick- Art of the Frame 2019).

It was also drawn to my attention that the background was painted in a different style to the portraits, and apparently with less skill, which created even more dissonance for the viewers. I found these comments very worthwhile, and it helped me further understand the key elements of my practice. It seemed that the compositional elements in my painting were working to achieve the desired effect, but I also felt that it was time to explore new avenues for doing so.

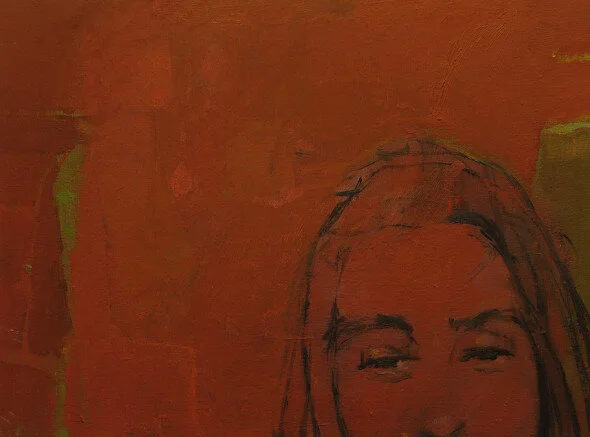

The next phase of my unit 1 research happened in tandem with preparing and thinking about my next painting. The cinematographic aspect of my painting and the way distortion of space could affect the feeling of the painting were two key elements of exploration for me during this time. I had been looking at a lot of work by Nelson Diplexcito, drawing inspiration from his use of harsh filmic lighting, and especially of colour in his paintings. For example, one of his portraits is painted primarily in red. In an interview I conducted with him, he explained how the use of colour in his painting was not premeditated, but came about as a way of transforming a painting while making it. I also found out that he was a film director and photographer prior to becoming a painter, and that he also worked mainly from his own photographs as source material. I took several photographs of my boyfriend using a red light, in his living room, to experiment with colour. I wanted to start thinking about creating a body of work rather than a single painting and play with the idea of narrative using different paintings almost as film stills. Some of the resulting photographs did not include the whole figure, for instance showing only a pair of legs on a sofa. Although I found that the photographs worked even perhaps as standalone works, a crucial part of painting for me is the transformation of the image once it starts taking life on the canvas. Despite very carefully setting up my source material, I have a much looser approach to the painting process, where I the painting process guide my hand.

Nelson Diplexcito

Max Beckmann, Self-Portrait in Bowler Hat, 1921.

During a recent one on one session, I was pointed in a direction I had not thought of before. I started to see my work in a different light, looking in particular at Max Beckmann, and themes of alienation and the human experience. Beckmann’s painting was informed by the war, and through his distorted portraits he sought to:

‘to make the invisible visible through reality,’ suggests[ing] that the significance of his work transcends his realistic subject matter, requiring a deeper reading of the subjects which that populate his art (Weitman 1995, p. 18)

The more I read about him the more I started to think about my work and what I was attempting to convey through it, and how my thoughts and experiences shape my painting style. It made me realise how I could use distortion not just of the background but of the figure, and cropping to focus in on the psychological aspect of the figure, as Max Beckmann did in Self-Portrait in Bowler Hat. Here:

The poignant expression lends a mystery to the image as his penetrating gaze engages the viewer. It alludes to a reality deeper than surface appearances. His face is tightly framed by the cat on the left, the vase on the right, and the imposing hat above, sharpening the focus. (Weitman 1995, p. 19)

Further researching these elements, I turned to a favourite artist of mine, Lucian Freud, and then to Francis Bacon who I was less familiar with, to see how their work was also extremely influenced by their experience of society at the time, and how they sought to depict what they saw as the human condition in their portraits (albeit in different ways). In his essay, Bacon- Psychoanalyst for human solitude, Carelli (2009, p. 77) explains how:

His paintings of the 1940s bore witness to the shattered psychology of the time […]. He captured sexuality, violence and isolation in his unflinching depictions of the anxieties of the modern condition.

Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953.

The painting Study after Velásquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X has fascinated me for a long time, no doubt because of the raw, unforgiving depiction of an almost primal scream. Bacon was inspired by a photograph of a nurse from Eisenstein’s film, Battleship Potemkin (Carelli 2009, p. 77). This relationship between photography and film is one I find fascinating, and Bacon’s explanation of how he used photography no doubt helped his artistic endeavours:

One of the great sources (…) of Bacon’s originality as an artist is that perhaps taking his starting point from surrealism he did actually come to appreciate more and more how a painter could look at the photograph and use it for his own very different ends. (Centurions: 54: Francis Bacon: Innocent Screams 1999).

As someone who uses photography as my source material, I am fascinated by how painting can be used to transform a photograph and become its own I age with its own meanings, as with Bacon’s use of the Battleship Potemkin photograph. As Bacon puts it, this power of painting stems for me from the fact that “When you paint anything you are also painting not only the subject, you are painting yourself as well as the object that you are trying to record,” (Centurions: 54: Francis Bacon: Innocent Screams 1999).

References

Carelli, F., 2009. Bacon – psychoanalyst for human solitude. London Journal of Primary Care, [online] 2(1), pp.77-77. Available at: <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/17571472.2009.11493252> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Centurions: 54: Francis Bacon: Innocent Screams, 1999. [TV programme] Radio 3: BBC.

Diagnostics, F., 2019. Stanley Kubrick - Art of the Frame. [video] Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HazR58qlcyo&ab_channel=FilmDiagnostics> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Freud, S., 1919. The "Uncanny". [ebook] pp.1-21. Available at: <https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf> [Accessed 5 February 2021].

Glass, N., 2017. Gregory Crewdson captures the dark side of rural America. [online] CNN. Available at: <https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/gregory-crewdson-photographers-gallery/index.html> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Hubbard, S., 2010. Exposed Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera Tate Modern London – Sue Hubbard. [online] Suehubbard.com. Available at: <https://suehubbard.com/exposed-voyeurism-surveillance-and-the-cameratate-modern-london/> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Nieves, E., 2020. Film Technique: Chiaroscuro in David Lynch's Mulholland Drive — A-Bitter Sweet-Life Studios. [online] A-BitterSweet-Life Studios. Available at: <https://www.abittersweetlifestudios.com/expressway/2020/1/27/the-chiaroscuro-technique-in-david-lynchs-mulholland-drive#:~:text=Chiaroscuro%20translates%20to%20%22light%2Ddark,oscuro%3A%20dark%20or%20obscure).> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

O'Hagan, S., 2017. Cue mist! Gregory Crewdson, the photographer with a cast, a crew and a movie-sized budget. [online] The Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/jun/20/gregory-crewdson-photographer-cathedral-of-the-pines-appalachians> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Sheen, E. and Davison, A., 2004. The Cinema of David Lynch: American Dreams, Nightmare Visions. London: Wallflower Press, pp.96-99.

Sherwin, S., 2018. Edward Hopper’s Night Windows: evoking voyeurism and intrigue. [online] The Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/feb/02/edward-hoppers-night-windows-evoking-voyeurism-and-intrigue> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Weitman, W., 1995. A Disturbing Reality: The Prints of Max Beckmann. MoMA, [online] 19, pp.18-19. Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4381287?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents> [Accessed 9 February 2021].

Willemsen, S. and Kiss, M., 2019. Last Year at Mulholland Drive: Ambiguous Framings and Framing Ambiguities. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, [online] 16(1), pp.129-152. Available at: <https://content.sciendo.com/configurable/contentpage/journals$002fausfm$002f16$002f1$002farticle-p129.xml?tab_body=pdf-79694> [Accessed 9 February 2021].