Towards the end of Unit 2, I was examining the relationship between the male and female figure on a canvas and trying to find ways to visually express the tension of couple dynamics. The couple whom I used in my first painting on this course (Unit 1) were willing to pose for a series of photographs for my planned work for Unit 3. Since the woman is expecting I thought that could add another interesting element to the couple dynamics I was trying to represent. My process always starts from a photograph. For the photographs, I had the couple sit on a small sofa, otherwise known as a loveseat, in their apartment, and took them from a slightly raised perspective. I instructed them both to wear casual/formal clothing, something they would wear if people were coming over.

I had them participate in choosing the poses they would take, with the instruction to take certain poses that could express a tension between closeness/distancing. Once we had taken multiple photographs with various poses, though with the same neutral facial expression in all of them, I selected one to use as source material for my first painting of Unit 3.

Bea and Kevin test photos.

The simple pose of the couple sitting on the couch side by side interested me, as I thought that just having a couple sitting in close proximity without looking at each other could allow the viewer to construct a narrative around the couple’s relationship. I also thought that the little information on what space they were in, due to close cropping, would lead one to question the setting of the painting. For example, it could take place in a home, in a counsellor’s office, or they could be acting in a play…

During one of the critiques, it was suggested that I read The God of Carnage by Yasmina Reza, a play which highlights the tension of marriage and intimate relationships. The premise is that two couples convene to discuss one of their sons hitting the other, and slowly devolve from forced civility to reveal cracks within their couple relationships and the veneer of propriety. The play’s take on matrimony can be summed up as such: “What I always say is, marriage: the most terrible ordeal God can inflict on you.” (Reza 2008, p.48).

In addition to thematically linking to my work, I found it appropriate that the stage directions at the start of the play visually corresponded to my painting: “A living room. No realism. Nothing superfluous” and “The Vallons and the Reilles, sitting down, facing one another.” (Reza 2008, p.2-3).

The God of Carnage, Theatre Royal, Bath, 2018.

Furthermore, on a deeper level this play dives into questions about masculinity/femininity and family roles, as well as questioning the role of the family unit and the importance of procreation: “children consume and fracture our lives. Children drag us towards disaster, it’s unavoidable. When you see those laughing couples casting off into the sea of matrimony, you say to yourself, they have no idea, poor things, they just have no idea, they’re happy. No one tells you anything when you start out” (Reza 2008, p.49).

Reza poignantly expresses one’s of the husband’s view of his role in the family unit, saying that “women always think you need a man, you need a father, as if they’d be the slightest use. Men are a dead weight, they’re clumsy and maladjusted” (Reza 2008, p.14). This is at the same time an absolution of his need to participate in family matters such as discussing his child’s problems, but could be read as an unfortunate confusion as to the role men are supposed to play in a family and society at large. My painting of the couple (Unit 3 artwork) could point to this dichotomy, where the man is slightly turned away, looking elsewhere, as if shirking his responsibilities towards his pregnant wife. In turn, the woman look at us head on, accepting her responsibility within the family unit. Reza expresses through the line “you’re a mum Annette. Whether you want to be or not. I understand why you feel desperate.” (Reza 2008, p.28) the inescapable burden of the female within the family unit. As such, we can imagine that the woman in my painting is both accepting and quietly pleading for rescue from the burden of motherhood, which her male partner will never have to know.

To better understand this idea of couple dynamics, and the potentially dark hidden truths in an individual and subsequently in any partnership or family, I began to look at the concept of shadow work by Carl Jung. The shadow self is the part of the self that is kept hidden:

One might define the shadow as referring to the darkness of the unconscious, to what is rejected by consciousness, both positive and negative contents as well as to that which has not yet or perhaps will never become conscious. Turning toward this darkness means facing the unacceptable, undesirable, and underdeveloped parts of ourselves … as well as discovering the potentials for further development of which we are unaware (Marlan 2010, p.5-6)

In the context of a heterosexual relationship, the shadow could refer to the part of the woman which does not desire to be a mother, even in the context of being pregnant. For the man, it could be that he secretly wants to live a life free from any duty towards a potential family unit, even though society expects him to provide. To accept the shadow is a difficult process: “Stein notes that coming to terms with the shadow means “calling into question the illusions one clings to most dearly about oneself, which have been used to shore up self-esteem and to maintain a sense of personal identity” (Stein 1995, 40)” (Marlan 2010, p.5). However, one could argue that the shadow parts in an intimate relationship must be shown and understood to better know the other, and to have a true partnerships based not off the solely conscious needs and desires but everything that lurks beneath the surface. Another idea I had for this notion of the couple is that one seeks a partner who maybe reflects the shadow self that we judge within ourselves. For instance, a woman who secretly harbours a desire to reject her wifely or motherly duties may openly criticise a husband for not spending enough time with the family.

This research into the shadow self led me to create a triptych as my final series of work for this course. The idea of this triptych for me was to highlight the idea of integrating and showing one’s shadow in an intimate relationship. The middle painting, where both members of the couple are present, shows the side of them that they want to be shown, the socially acceptable side while the shadow lies beneath the surface. Then, each individual receive their own space and can show their shadow. They are free to lie or sit on the couch as they would without the other, as the shadow starts to appear:

The shadow’s trickster-like behavior acts as if it had a mind of its own, sending conscious life into a retrograde movement, where something other than personal will seems to hold sway. The shadow appears as well in dreams … on the one hand resisting consciousness, on the other seems to be pursuing it by seeking confrontation, challenge and threat, often leaving the person terrified and retreating from contact (Marlan 2010, p.6)

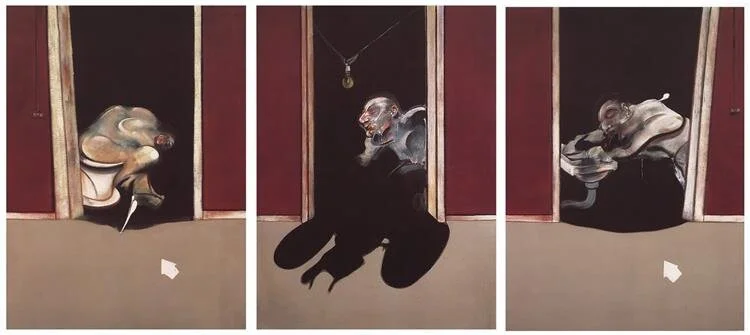

To give a visual nod to the shadow in my triptych, I used solid black shadow beneath the couch, also as a way of anchoring the object. The idea of the shadow as a visual concept led me to examine Francis Bacon’s use of the shadow. For Bacon, the shadow holds an integral place in figure painting: “Bacon has often said that, in the domain of Figures, the shadow has as much presence as the body: but the shadow acquires this presence only because it escapes from the body; the shadow is the body that has escaped from itself through some localized point in the contour” (Deleuze 2017, p.11-12).

Triptych May-June 1973, Francis Bacon, 1973.

We can interpret this use of the shadow as a visual element as being the shadow self as Carl Jung interprets it escaping from the individual in Bacon’s work. While serving this purpose, the shadow was also used by Bacon as a tool to isolate his figures in space: “a Figure is isolated within a ring, upon a chair, bed, or sofa, inside a circle or parallelepiped” (Deleuze 2017, p.3) and “in short, the painting is composed like a circus ring, a kind of amphitheater as ‘place.’ It is a very simple technique that consists in isolating the Figure” (Deleuze 2017, p.1).

In terms of these techniques of isolation in my own work, the couch serves as an isolating element, where the figures are confined to it, and in the case of the one with the male figure almost painfully so. The shadow at the bottom of the couch serves to locate figures in space, and the flat colour planes of the floor and wall behind the couch to give a certain anonymity to the environment: “they are not beneath, behind, or beyond the Figure, but are strictly to the side of it, or rather, all around it” (Deleuze 2017, p.3).

Another important visual element of this series, or rather, an important object, is the couch. I chose the couch at first because it seemed like a neutral object, something one would naturally find a couple sitting on. However, I quickly began to realise the implications of depicting such an object particularly in a series highlighting the inner life of the individual in coupledom. To ignore the couch’s association with psychology would be to disregard a seminal part of its history as an object, and “indeed, more than any other setting element, the couch seems to be the lasting Freudian inheritance” (Lingiardi & De Bei 2011, p.390). The reasons for the couch being so important to psychology are the following: “Ogden considers the couch an essential component of the support structure of psychoanalysis, providing the conditions of privacy necessary for the analyst to enter a state of reverie and give himself up to the flow of thoughts” (Lingiardi & De Bei 2011, p.394-395). Moreover, “the couch and the armchair can be used in analysis to preserve a sense of safety and to defend against fear” (Lingiardi & De Bei 2011, p.397) which leads one to think of it as a safe space of sorts, which is ironic in that the lying down position of psychoanalysis is one of the most vulnerable.

As well as a place of vulnerability and paradoxical safety, being on the couch can also lead to feelings of isolation: “On this subject, Aron says that ‘There have been times when patients have told me how isolated they have felt on the couch …(Aron, 1996, p. 142)” (Lingiardi & De Bei 2011, p.397). This is unsurprising given that the patient in psychoanalysis is not facing the psychoanalyst while expressing vulnerability. One can attribute all of these interpretations to my painting of the male figure reclining on the couch.

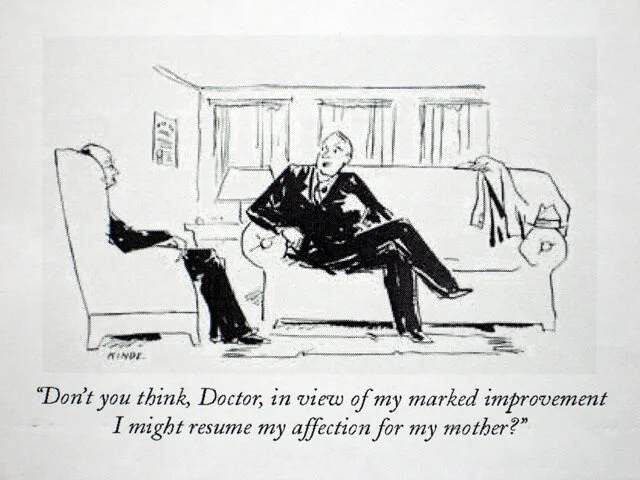

Particularly while working on this second painting, I continued to think about the significance of this object and its use as a visual cue to imply certain narratives to my series: “in any case, it’s clear that even among people with little or no interest in psychoanalysis, or any other form of "talk therapy", the couch is an icon that is immediately understood to stand for psychotherapy or, more generally, self-understanding” (Shackle 2017, para.3). As Shackle aptly puts it, there can be an almost caricatural element to the couch as a cultural icon and its representations in the context of introspection: “couch cartoons mock our narcissism, our self-absorption, our imperiousness, our fears, our neediness. In this sense, they show a private self at work: disclosing, ruminating, obsessing, expressing. Recumbent speech puts everything into play, so to speak” (Shackle 2017, para.7). This shows the double-edged sword of self-discovery and inner work, which in turn could also be construed as the shadow self, which is the potentially more narcissistic side on the individual.

Freud Museum.

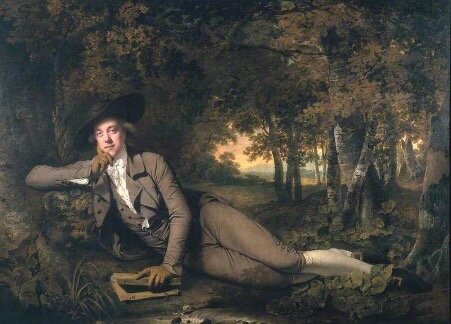

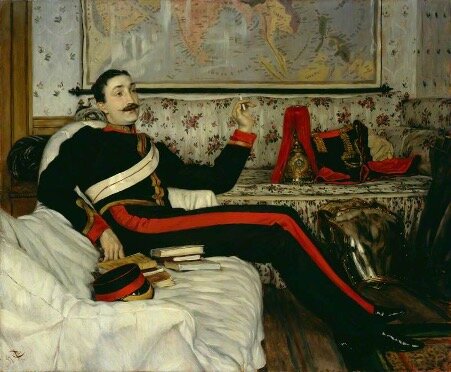

Not only is the couch significant in the second painting with the male figure, but his pose is as well: “the reclining figure is one of the most popular poses in art history. It is firmly embedded within western and eastern art historical traditions” (Figes & Shore 2019, para.5).

The choice to represent a man reclining on a couch in particular holds some historic weight to it. Traditionally, reclining figures throughout art history have been female, with some notable exceptions for men of high-society, as we can see in the following works. This idea is another culturally embedded cue people have upon seeing a figure reclining on a couch. I began to think even more deeply about this notion of masculine and feminine, and the interaction between the two, and how the choice to represent a couple posing in a certain way could be interpreted. Although each member of the couple gets their own portrait in my triptych, the man is the one lying down in his most vulnerable state, almost on alert. I chose to title this painting “Waiting.” To convey the ambiguity of the multiple potential narratives: waiting for his wife, for a therapist, or maybe even to be waited on. This last interpretation could stem from the fact that “reclining figures have sometimes historically conveyed a sense of entitlement, elite status and power. The posture gives the impression that somebody is being waited upon, attended to, or served” (Figes & Shore 2019, para.7).

Sir Brooke Boothby, Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797),

Frederick Burnaby, James Tissot (1836–1902).

This pose of the lone man, waiting for something, also ties into the notion that men are naturally loners, that to be a man means to not need anything or anyone, a stereotype also perpetuated by women as Reza aptly references when one of the mothers expresses her feeling that: ‘a man ought to give the impression that he’s alone… If you ask me. I mean, that he’s capable of being alone…! […] A man who can’t give the impression that he’s a loner has no texture…” (Reza 2008, p.58).

The female portrait which I worked on as my final piece this year shows the woman in an erect position on the couch, but slightly turned away from us. She is pregnant, and the pose implies some level of strength but also vulnerability. She is strong but at the same time appeasing, she has something of the fantasy of motherhood, especially in my first painting with the couple side by side. Her expression is almost Madonna like, serene, the idea that men or society might have of the mother figure. Paula Rego’s work encapsulates this idea of the strong yet peaceful woman: “the fetishistic redress of a lack (she must appease even as she threatens), or as a vehicle of genealogical reproduction, borne out especially in the traditional iconography of the Madonna and Child. Both ideals had for centuries informed traditional representations of women, pandering to male anxieties of loss of mastery” (Rosengarten 2016, p.4).

This notion of the roles we play as male and female is very present in Paula Rego’s work, and she subverts the family dynamic in her imagery and makes something dark out of family scenes. The scenes occurring within the supposed comfort of home hold a dark truth to them, which I have also attempted to convey in my series:

If, for Freud, the uncanny – the unheimlich – is the name for everything that is unremembered but not forgotten, that ought to have remained secret and hidden but that has, instead, come to light, then unnervingly, its opposite, the heimlich or homely is the condition in which all that is secret and hidden must persist so. The homely is the breeding place of secrets (Rosengarten 2016, p.2-3)

The painting The Family (Rego 1988) really exemplifies the sinister family dynamics present in Rego’s work. Obviously the title is leading, letting us understand that there is a disconnect between the scene being portrayed and the idea of what the word “family” represents. This scene is uncomfortable to look at, notably because of the explicit yet restrained violence of the act being carried out by what we presume is the mother and one of the daughters on the father as the other daughter keeps watch. This painting flips the notion of male dominance and patriarchy. The father is being subdued and overpowered by two females of the family, and as he glares at the one daughter his wife looks at her with sweet complicity: “concomitantly, in the home, Rego’s figures also stage a political drama. Here, we see the staging of the relationship of subordinates to superiors, a relationship that, in Rego’s work, paradoxically both endorses and reverses traditional gender roles” (Rosengarten 2016, p.3).

The Family, Paula Rego, 1988.

It is the expression of the mother and the daughter near the window which really gives an almost unreal feeling to the scene being played out. There is a sort of feminine softness and sweetness in their expression which at the same time seems to absolve them of their act but makes the intent feel even more violent, as if they are sweetly choking the father figure.

Another notable element of the painting is the way shadows are used to surround and highlight the figures on the bed, drawing the eye to them, while also the daughter near the window’s shadow stretches out, almost like the figure of Christ would at the altar of a church. There seems to be some sort of religious significance to her pose and the reference of her shadow, as well as her expression of sweet benevolence not unlike a cherub or the Virgin Mary.

I am very interested in Rego’s conception of the mother figure, and in my final painting of my series where the pregnant female sits alone on the couch I attempted to express this concomitantly peaceful and uneasy idea of the female as mother through such elements as distortion of proportions. Rego’s ideas surrounding this notion of motherhood can be summed up as follows: “while this relation of the female subject to male/paternal authority suggests that Rego might idealise maternity, even the most casual perusal of her work reveals ambivalence towards motherhood, figured not as the ‘connivance’ between a girl and her mother, but as the power to destroy” (Rosengarten 2016, p.4).

Although this painting depicts a somewhat more explicit family disconnect than my portraits, I am interested in the way the figures are together but also disconnected from each other despite physical closeness, at the same time playing out the dynamics amongst each other but also lost in their own world, as if they didn’t really have a choice of the roles being enacted.

All throughout this unit I have also been questioning the materiality of the paint itself and the choices in terms of mark making for the representation the figure. I am interested in conveying a sense of stillness in my paintings, but also of something going on beneath the surface, to provoke the same sensation as Bacon in his paintings: “what directly interests him is a violence that is involved only with color and line: the violence of a sensation (and not of a representation), a static or potential violence, a violence of reaction and expression” (Deleuze 2017, p.xi).

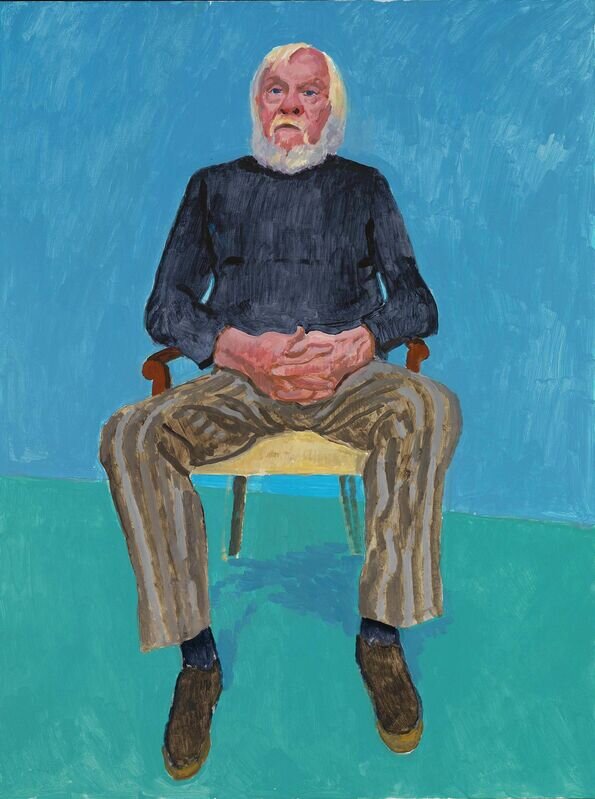

To learn more about different painting styles for portraiture, especially for representing clothing, I’ve observed several David Hockney portraits. This one of John Baldessari (Hockney 2013) interested me since it is painted quite quickly. I struggled trying to represent detail in clothing, and here we see that Hockney has decided to give very little information in terms of folds in the clothing. The lack of information and quick brushstroke actually give a feeling of movement and illusion of natural weight to the clothing. As for the way he depicts hands, which I have also struggled with in my paintings, we can see that he has not strived for an exact depiction. On the contrary, there is even a distorted element to the fingers, where they seems to almost be boneless and not follow the natural direction of a hand, yet this distortion does not distract from the overall feeling of the portrait. In my painting of the male figure lying on the couch, I have decided to leave the hands a little distorted, since I wanted the proportions of my figure to be a little off to create discomfort.

John Baldessari (13th-16th December 2013), David Hockney.

This well-known painting of Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd by Alice Neel (1970) has also inspired me throughout this series. It features a couple on a couch, and a feeling of together yet alone-ness. The distortion in proportions, particularly of the man’s legs, directly inspired my first portrait of the series. I am fascinated by how Neel chooses to omit detail or hone in on it at the same time at different places in her painting. For example, one hand will be quite detailed with joints drawn in, albeit unnaturally proportioned, and the other on the leg will have a cartoonish aspect to it. It is this interplay between highlighting and omitting that adds energy to Neel’s work, as well as the use of bold colour. In my own series, I chose to represent the female figure’s hands in more detail as they are wrapped around the pregnant belly, in the painting of her alone they could almost have a gripping quality to them, adding the ambivalence of the unfolding scene.

To close off this series of paintings, I plan to execute a final piece where the couple is together on the canvas again, this time to express the coming together of the shadow selves. The male figure will be lying with his head resting on the woman’s lap, as she takes on the familiar female role and comforts him while also seeming to be distracted from her duties, looking away and shying from responsibility for the man’s feelings.

Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd, Alice Neel, 1970.

Professional Skills & Career Path

I would like to continue exploring the theme of the couple, the masculine/feminine roles, and the inner dynamics of the human psyche through different forms in the future. Perhaps as the couch has its own cultural significance, so too can an object such as an armchair, a bed, or even a bathtub. The neutral or private significance of certain objects to the life of a couple is of great interest to me. I feel as though I have progressed in my research and in the way I visually express my ideas throughout this course. Having completed a series of work for Unit 3, I feel I have a solid base for future research, combining my longstanding interest in psychology and portrait/figure painting. I have also noticed an evolution in my painting style as the course has progressed, and even within the works in Unit 3. At first I felt restrained in my brushstrokes, which might reflect the atmosphere of the scene I was working on, but by the final painting (female figure), I felt more loose and able to more confidently mark make. It is my hope that I can continue to evolve my painting past this course, to find a style which best suits my desire to highlight the inner workings of my portrait subjects.

This course has truly allowed me to hone my research and practical skills, and the numerous presentations of practicing artists throughout the year have allowed me to see that working as an artist is possible. However, I can also see that financial stability is not always a guarantee as an artist, which is why I am interested in either working alongside a gallery as an assistant while continuing my art practice on the side, or going into teaching, as it allows for continuing growth as an artist while being surrounded with new ideas from fellow artists (at higher level teaching). I am still unsure of what the future holds, and the limits of the pandemic on our course this year have made it difficult to envision a future career path, though the presentations have allowed me to see that there is a huge variety in types of art or in ways people incorporate their interest in different fields into their artwork. As psychology remains a passion of mine, I am keen to continue learning how to combine this with art. Another interest of mine which has been suggested by many is the field of art therapy. I do believe art can be extremely therapeutic and I also believe that there is a form of releasing one’s inner demons onto a canvas that can be very freeing.

References

Academy of Ideas (2020). How to Integrate Your Shadow - The Dark Side is Unrealized Potential. [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tIoJhqnOc0M&ab_channel=AcademyofIdeas [Accessed 29 Aug. 2021].

Deleuze, G. (2017). Francis Bacon : The Logic of Sensation. Translated by D.W. Smith. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Figes, L. and Shore, A. (2019). The art of lying: reclining figures through history | Art UK. [online] artuk.org. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-art-of-lying-reclining-figures-through-history# [Accessed 29 Aug. 2021].

Hockney, D. (2013). John Baldessari, 13th-16th December 2013. Artsy.

Lingiardi, V. and De Bei, F. (2011). Questioning the couch: Historical and clinical perspectives. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 28(3), pp.389–404.

Marlan, S. (2010). Jungian psychoanalysis : working in the spirit of C.G. Jung. Chicago: Open Court, pp.5–13.

Neel, A. (1970). Jackie Curtis and Rita Redd. Financial Times.

Rego, P. (1988). The Family. Art Basel.

Reza, Y. (2008). The God of Carnage. Translated by Christopher Hampton. London: Faber and Faber Limited.

Rosengarten, R. (2016). Introduction. In: Love and Authority in the Work of Paula Rego: Narrating the Family Romance. Manchester University Press.

Shackle, S. (2017). Why does psychoanalysis use the couch? Q&A with Nathan Kravis, author of “On the Couch: A Repressed History of the Analytic Couch from Plato to Freud.” [online] newhumanist.org.uk. Available at: https://newhumanist.org.uk/articles/5246/why-does-psychoanalysis-use-the-couch [Accessed 29 Aug. 2021].